Having the right individuals in the boardroom is critical. Directors need to have the skills and experience that align with the company’s long-term strategy. Diverse and fresh perspectives are also important. While boards have been focusing on these topics, other areas like director tenure and succession planning are often addressed only when the board needs to replace a retiring director. This is not overly surprising considering they can be sensitive topics. So how should boards be thinking strategically about their board composition — now and in the future — to ensure optimal performance? They can take the following actions:

|

Make board refreshment and succession planning priorities on the agenda

|

Assess skills and attributes, and incorporate results from performance assessments

|

Set directors’ expectations around tenure

|

|

Take a multi-year view toward departures and address upcoming leadership changes

|

Agree on a succession plan that prioritizes needs and build a talent pipeline

|

Shareholders and other stakeholders are paying increased attention to board composition. Institutional investors are putting pressure on boards to have a more rigorous process around board composition and refreshment. They are asking whether there is enough diversity in the boardroom, if the board has the right skills, how they think about director tenure and whether there is a succession plan. Many shareholders also want enhanced disclosure to better understand the board’s activities in this area. And, hedge fund activists have focused on board composition as part of their campaigns.

Boards don’t always make sufficient time on their meeting agendas to discuss board refreshment and succession planning. Is their discomfort with the topic getting in the way of doing what’s best for the board?

In our experience, approaches to board refreshment and succession planning fall along a spectrum. Some boards are strategic and forward-thinking, while others are reactive — with multiple options in between. Our view is that boards benefit from a more strategic approach.

The board refreshment and succession maturity continuum

Where does your board sit on the curve?

|

REACTIVE |

PROGRESSING |

STRATEGIC |

| Board leadership and prioritization |

Board leadership does not prioritize refreshment and succession planning. It receives little focus and has no formal planning process.

|

Board leadership makes refreshment and succession planning a priority for the nominating/governance committee, which leads an annual planning process. There is limited awareness by the full board.

|

Board leadership makes refreshment and succession planning a priority. The nominating/governance committee leads a regular planning process that is discussed with and agreed upon by the full board.

|

| Assessment of director skills |

A board skills assessment may be done informally but is neither structured nor documented. The annual board self-assessment is viewed as a compliance activity and provides limited insight into any potential skill gaps on the board. Results are not incorporated into the board refreshment process.

|

A board skills matrix may be used periodically to identify skill gaps, and results from board assessments may be incorporated into the board refreshment process.

|

A board skills matrix is used consistently to identify current and expected skill gaps and updated annually. Board and director assessments are seen as a continuous improvement exercise and results are incorporated into the board refreshment process.

|

| Director tenure expectations |

The board does not set expectations for director tenure and related governance policies. Individual director tenure is evaluated infrequently and on a case-by-case basis.

|

The board has general conversations about director tenure, particularly as new directors join. The nominating/governance committee periodically considers issues related to individual director tenure.

|

The board sets clear expectations about director tenure, regularly reviews individual director tenure and determines the optimal mix of director tenure levels on the board (i.e., new directors, medium-tenure directors and long-tenure directors).

|

| Time horizon for departures |

Board refreshment is primarily driven by mandatory retirement age.

|

Nominating/governance committee takes an annual view of imminent director departures and leadership changes, usually focused on individual board seats.

|

Nominating/governance committee takes a multi-year view of anticipated director departures and leadership changes, focused on the overall aggregate tenure of the board as well as individual director tenures.

|

| Succession plan and candidate profiles |

Nominating/governance committee does not have a formal succession plan. A director candidate profile is developed only when a board vacancy is imminent.

|

Nominating/governance committee reviews the succession plan annually and maintains director candidate profiles. But search efforts are episodic and not linked to the overall succession plan to address prioritized skills and attributes.

|

Nominating/governance committee maintains a multi-year succession plan and director candidate profiles with a prioritized list of skills and attributes, and a talent pipeline is developed for future needs.

|

In practice: the board succession planning maturity continuum

Example: John Smith is on the board of ManufactCo. and will reach the board’s mandatory retirement age of 75 in approximately one year. He has a strong traditional manufacturing background and qualifies as a financial expert on the audit committee. Cheryl Jones will reach the mandatory retirement age two years after John. She has deep expertise in financial management and investment banking and also qualifies as a financial expert on the audit committee.

Reactive

The nominating/governance committee plans to begin searching for a director candidate in the next few months to find a replacement for John. The committee will seek a candidate with skills similar to John’s. The annual performance assessment survey did not reveal any substantive changes needed to overall board composition. Although several directors suggested skills that may be needed in the future, the committee chose not to memorialize this in a skills matrix.

Progressing

John’s departure was identified a year in advance during annual board succession planning, and the nominating/governance committee has spent that time discussing his replacement. The committee maintains and refreshes the board’s skills matrix each year. It concluded that the company’s digital strategy is becoming increasingly important and that a director with digital skills will be critical to board composition. The committee also noted the need for greater gender diversity, and the fact that several other board members qualify as audit committee financial experts. The nominating/governance committee created a candidate profile based on this information and has been soliciting ideas for director candidates to replace John next year.

Strategic

The nominating/governance committee has been preparing for John’s departure for more than a year. It is also planning for the vacancy that will be created when Cheryl reaches the mandatory retirement age two years after John. The committee reviewed the results of the board and individual director assessments to consider whether the skill sets of current directors are still relevant. It also regularly updates the board’s skills matrix as part of the succession planning process. This process identified digital skills in the manufacturing industry, gender diversity and operating experience as elements important to prioritize for overall board composition. The nominating/governance committee created candidate profiles with prioritized skills and attributes for both John’s and Cheryl’s successors. They discussed the succession plan and candidate profiles with the full board. The committee has been actively searching and interviewing director candidates to replace both John and Cheryl. The board’s skills matrix is disclosed in the proxy statement to provide greater transparency to investors.

“A strategic approach to board refreshment and succession planning will ensure that the board is positioned to be a strategic asset to the company.”

Maria Castañón Moats

Leader, Governance Insights Center, PwC

Make board refreshment and succession planning priorities on the agenda

Make board refreshment and succession planning priorities on the agenda

Implementing a strategic approach to board refreshment and succession planning requires effective board and committee leadership. For most boards, the nominating/governance committee oversees the process. This includes developing and recommending criteria for board composition, addressing director tenure, creating a succession plan and leading the search for new candidates. In addition to the committee, the full board should also understand, review and have input into the process.

Boards are unlikely to tackle these topics in a rigorous way unless it is explicitly part of their agenda. So it is critical to regularly carve out time on the nominating/governance committee and board agendas.

Board culture also has a role to play. The culture has to allow for frank and candid dialogue about board composition, director tenure, retirements and the need for different director skill sets. These are sensitive, difficult discussions, which make strong board leadership all the more essential.

Shareholders have heightened expectations about understanding the board’s approach to refreshment. They want to know whether a robust succession plan exists, whether it addresses skills needed in the future and how frequently the topic is discussed, among other items. Some boards are evaluating whether greater transparency on their approach would be valuable considering shareholders’ interest.

Assess skills and attributes, and incorporate results from performance assessments

Assess skills and attributes, and incorporate results from performance assessments

Nominating/governance committees further along the strategic board refreshment and succession maturity continuum compare the skills and attributes of current directors with those that are critical to the company’s long-term strategy to identify and address any gaps. If there are gaps, the board can add expertise or consider bringing in outside experts to fill the gap.

As companies are innovating, implementing new technologies and entering into new markets, their business models may call for directors with new or different skill sets. But boards shouldn’t focus on adding a director with just a singular new skill set (e.g., cyber or human resources). Directors need to be able to contribute in all areas of board oversight.

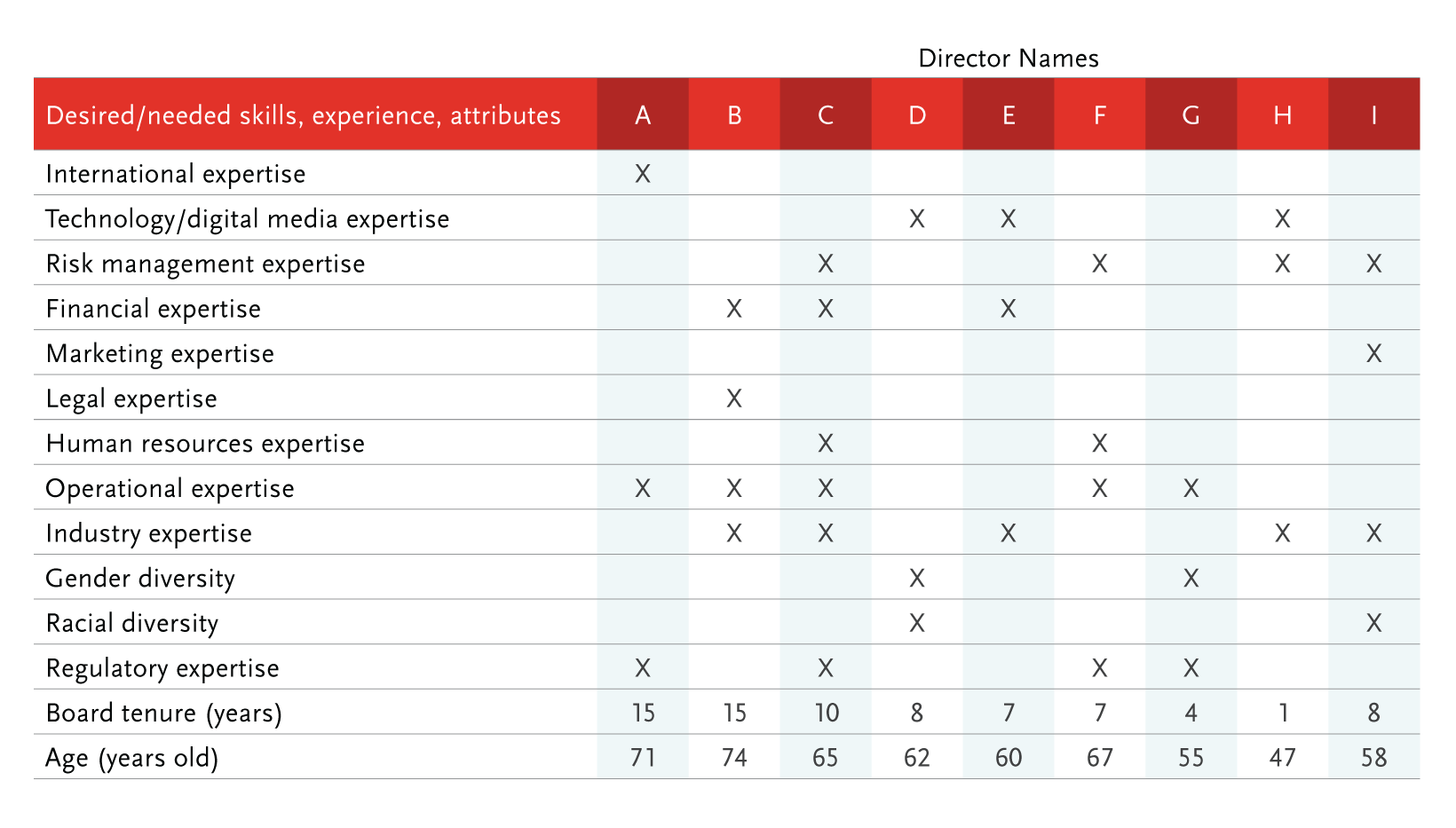

The committee should use board composition matrices or a similar tool to help them evaluate their skills and attributes, and include these items as part of their multi-year board succession plan. Boards further along the refreshment maturity continuum share the matrix with their full board for input and agreement. They may even voluntarily disclose these tables, or something similar, in their proxy statements.

Feedback from the annual board, committee and individual director assessments should also be incorporated into the board refreshment process. When assessments are done in a meaningful way, they can help identify whether new or different skills or greater diversity is needed.

38% of S&P 500 companies disclose a director skills matrix, in their

proxy statement.

Source: Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, December 2020.

Sample board composition matrix

As part of the board refreshment process, boards should understand institutional investors’ views about increasing diversity, particularly gender and minority representation, in the boardroom. Boards can also think about whether it would be beneficial to add younger directors (e.g., age 50 or under) to the board. There is a growing recognition that boards with a good mix of age, experience and backgrounds tend to foster better debate and decision making and less groupthink.

Many investors view the pace of change for board diversity as too slow. Some investors have raised their board accountability efforts by voting against the entire board of directors or the nominating/governance committee in director elections when board diversity is lacking. Various state lawmakers have also weighed in by enacting legislation requiring a certain number of board seats be held by women or diverse directors. But boards shouldn’t wait for investors or others to push for increased diversity. Instead, they should ensure that diversity is a board priority and address any factors preventing the board from making progress.

Board Action on Assessments

| Add additional expertise to the board |

|

|

| Change composition of board committees |

|

|

| Diversify the board |

|

|

| Provide disclosure about the board’s assessment process in the proxy statement |

|

|

| Use an outside consultant to assess performance |

|

|

| Provide counsel to one or more board members |

|

|

| Not re-nominate a director |

|

|

72% of directors say that their board has taken some action in response to their last assessment process

Source: PwC, 2020 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, September 2020.

Among S&P 500 Companies:

|

70%

report having a mandatory retirement age for directors

|

48%

of boards having a mandatory retirement age set their retirement age at 75 or higher

|

6%

set explicit term limits, with a majority of the policies set at 15 years or less

|

Source: Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, December 2020.

Set directors’ expectations around tenure

Set directors’ expectations around tenure

Boards further along the maturity continuum openly discuss and forge agreement on appropriate director turnover, and how it will be achieved. Board leadership sets the tone about the length of director service at the outset. They ensure directors understand that re-nominations are not simply assumed — they are based on the evolution of the company and board, and sustained high-performance at the individual director level.

In addition to setting clear expectations around director tenure, boards should periodically assess whether tenure-limiting policies are appropriate. Most boards rely on mandatory retirement policies to promote turnover. In some cases, boards make exceptions to mandatory retirement ages to keep a particular director on the board. This can become problematic as it can set a precedent for all future directors nearing retirement age. Term limits are much less common.

Another area that boards can focus on is the optimal mix of board tenure levels or aggregate board tenure. Some boards seek to balance their composition of new directors, those with medium tenures and those with long tenures.

But boards shouldn’t rely solely on tenure-limiting policies to drive turnover. The annual performance assessment can be an effective tool to evaluate board and individual director performance on a regular basis.

Some institutional investors and proxy advisory firms have also been vocal about director tenure. They are concerned about how tenure affects director independence, objectivity and the ability to challenge management. Boards should consider these views as part of their succession planning.

Don’t be left without an audit committee financial expert

Nominating/governance committees will want to ensure they have properly planned to always have at least one audit committee financial expert (ACFE), as required by SEC rulesa. Boards left without this critical expertise must note that fact in their disclosures, and explain why.

To avoid being left without an ACFE, many boards have an additional audit committee member who meets the financial expert definition.

aSEC rules, Disclosure Required by Sections 406 and 407 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8177.htm.

Take a multi-year view toward departures and address upcoming leadership changes

Take a multi-year view toward departures and address upcoming leadership changes

A key part of strategic board refreshment and succession planning is anticipating and proactively addressing planned and unplanned vacancies in the boardroom. Without a plan, the board may feel pressure to waive or change board policies, including mandatory retirement ages, or simply recruit a director with the same profile as the one retiring. This ad hoc approach doesn’t allow the board to think more broadly about alternatives that may result in a better fit or better board performance.

Boards further along the maturity continuum take a longer-term view — focusing three to five years

out — to effectively address anticipated departures. They create a waterfall chart that identifies all directors, their skill sets and expertise, their board roles (including leadership and committee membership), board tenure, the year they would likely be leaving the board based on expected retirement and other factors.

This broader view gives the nominating/governance committee ample time to effectively plan and recruit the right candidate and have a smooth transition.

It is equally important to address the prospect of unexpected turnover, particularly for those directors serving in leadership positions. A plan that considers the potential for such an event to occur positions the board to fill vacancies more quickly.

Top three backgrounds of individuals serving board leadership roles

Lead and presiding director

-

Retired CEOs/chairs/vice chairs/presidents/COOs

-

Investment manager/investors

-

Other corporate executives

Audit committee chair

-

Financial executives/CFO/treasurers

-

Retired CEOs/chairs/vice chairs/presidents/COOs

-

Public accounting executives

Compensation committee chair

-

Retired CEOs/chairs/vice chairs/presidents/COOs

-

Other corporate executives

-

Investment managers/investors

Nominating/governance committee chair

-

Retired CEOs/chairs/vice chairs/presidents/COOs

-

Investment managers/investors

-

Other corporate executives

Source: Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, December 2020.

“The process of identifying potential director candidates, vetting them and reaching out to them to share the board’s interest can take many months. Boards that plan well in advance will be in the best position to find the right director candidates that address the board’s future needs.”

Julie Hembrock Daum

Leader, North American Board Practice, Spencer Stuart

For leadership changes due to retirement, committee chair rotation or other reasons, an existing board or committee member is often chosen as successor. This is because the individual already has institutional knowledge of the company, familiarity with the key issues and relationships with the other board or committee members and management. While the successor has this information, leading practice when there is an expected leadership change is for this individual to have a six-month to one-year time period to “shadow” the current leader and obtain deeper insights into the role.

Board leadership roles can’t be filled by just anybody on the board. Effective succession planning by the nominating/governance committee should ensure new board leaders have the right skills, time and commitment to perform the role. Board and committee leaders set the tone in the boardroom. They have to be able to promote effective working relationships, handle conflict and be strong facilitators. Specialized knowledge and experience are also critical for audit and compensation committee chairs in order to address the technical issues handled by these committees. Boards also need to take into account regulatory requirements for certain skills — such as financial expertise on audit committees — that will need to be considered when addressing leadership succession.

Agree on a succession plan that prioritizes needs and build a talent pipeline

Agree on a succession plan that prioritizes needs and build a talent pipeline

Strategic board refreshment will bring in discussions around director departures, tenure evaluation, skill set assessment and performance assessment results to agree on a multi-year succession plan.

Nominating/governance committees will want to collectively debate, prioritize and settle on the board’s future composition needs and a timeline for changes. The key is to be agile and allow the board to make changes as situations or needs arise. For example, some boards have expanded their size to make composition changes faster or to provide an opportunity for a director candidate to shadow another director during a transition period.

Ultimately, the board succession plan and priorities should be reviewed and agreed to by the full board. This action helps the board understand the full complement of directors and how each individual director’s skill set and attributes are relevant to the company. It can help directors understand new skills needed in the boardroom, identify potential future directors, and may be an impetus for further education and skills development for existing directors.

Being realistic: you can’t have it all in one candidate

Boards frequently prioritize their need for an active CEO and diverse candidate, but not every board can attract the highly sought-after sitting CEO who is a minority or a woman. The pool of candidates meeting these criteria is small, and many of these individuals already have board commitments. Only 6% of CEOs are female at S&P 500 companies, and only 10% of CEOs are African-American, Hispanic/Latino or Asian at the largest 200 companies.b

b Source: Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, December 2020.

When identifying the board’s needs for future director candidates, it is important to be realistic. Boards can fall into the trap of creating a “laundry list” of attributes, desired skill sets and expertise that is unlikely to be filled by one director candidate. Instead, ranking what is most important can make it easier to find appropriate candidates and choose among multiple candidates.

Boards further along the maturity continuum look not only for a candidate they need now, but also proactively build relationships with potential candidates to develop a talent pipeline. Some boards keep a running list of potential director candidates for future reference. Directors should utilize approaches that look beyond asking other sitting directors for recommendations to find their next board candidate.

The Changing Profile of New S&P 500 Directors

| Diverse directors (women and minority men) |

|

|

| Serving on their first public company board |

|

|

| Next-gen directors, 50 years old or younger |

|

|

Source: Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, December 2020.

Conclusion

Boards should strive to move up the board refreshment and succession maturity continuum toward a strategic approach. A strategic approach delivers benefits to board performance and increases long-term shareholder value. At its best, board refreshment and succession planning is an iterative process that takes into account the company’s evolving business model and the changing governance landscape. This is increasingly important as investors continue to seek greater transparency around the board’s activities in this area.

Appendix: Diversity and tenure proxy voting guidelines for select shareholders and proxy advisory firms

BlackRock1

Diversity

-

Expects boards to be comprised of a diverse selection of individuals. This diversity includes multiple dimensions.

-

Encourage companies to have at least two women directors on their board.

Tenure

-

BlackRock is not opposed in principle to long-tenured directors, nor do they believe that long board tenure is necessarily an impediment to director independence.

-

A variety of director tenures within the boardroom can be beneficial to ensure board quality and continuity of experience.

Nuveen2

Diversity

-

Consider voting against nominating and governance committee members when there is no gender diversity on the board.

Tenure

-

Consider voting against nominating and governance committee members when the average tenure is greater than 12 years and there has been no refreshment in the last five years. A mix of director tenures can support a board’s overall quality of composition, continuity and independence.

CalPERS3

Diversity

-

The board should understand the necessary aspects of diversity required to effectively oversee management’s execution of strategy.

Tenure

-

The board should consider whether a director’s tenure compromises their independence. CalPERS’ policy specifically states that they “believe director independence can be compromised at 12 years of service.”

CalSTRS4

Diversity

-

Diversity should be considered by the board or the nominating committee. This diversity includes many elements.

-

CalSTRS will hold members of the board’s nominating and governance committee and if necessary the entire board accountable if, after engagement about the lack of board diversity, sufficient progress has not been made in this regard.

Tenure

-

An effective board should have both short- and long-tenured directors to ensure that fresh perspectives are provided and that experience, continuity and stability exist on the board. CalSTRS does not support limiting director tenure but believes the board should regularly review the average tenure of the board and consider policies and procedures to encourage board refreshment as part of the annual board review.

ISS5

Diversity

-

Generally make voting recommendations against or withhold from the chair of the nominating committee (or other directors on a case-by-case basis) at companies in the Russell 3000 or S&P 1500 indices where there are no women on the board. A few mitigating factors are noted.

Tenure

-

ISS views a director with a tenure of more than nine years as potentially impacting director independence

-

Take a closer look when making voting recommendations at boards where average tenure of all directors exceeds 15 years in contested elections.

Glass Lewis6

Diversity

-

Generally recommend voting against the nominating committee chair of any board with no women directors. However, Glass Lewis says they will consider a board’s disclosure around diversity when making that recommendation.

Tenure

-

Glass Lewis does not endorse specific tenure limits. Rather, they encourage shareholders to monitor the board’s overall composition.

1 BlackRock, Corporate governance and proxy voting guidelines for U.S. securities, January 2020.

2 TIAA, “TIAA Releases Updated Policy Statement on Responsible Investing,” April 3, 2019.

3 California Public Employees’ Retirement System, Total Fund Investment Policy, September 2019.

4 California State Teachers’ Retirement System, Corporate Governance Principles, November 2018.

5 Institutional Shareholder Services, Proxy Voting Guidelines, November 2019.

6 Glass Lewis, 2020 Guidelines: United States, 2019.