December 29, 2017

The Benefits of Change: Five Ways Third Sector Boards Can Become More Effective in the New Year

The start of a new year is the perfect time for self-examination, reflection and resolutions to shed bad habits and begin fresh.

That sentiment of renewal applies to people, of course, but also to organizations. For organizations of the third sector in particular, one area that warrants resolution is the lack of alignment between leadership teams and their boards of directors. An effective international non-governmental organization (“iNGO”) board is increasingly important in today’s challenging environment, where the sector itself is being significantly disrupted. From waning government funding to fierce competition for private sector resources, to the disruptions of how social impact and responsibility have shifted investment — these are a sampling of the rapid changes occurring in the sector. As a result, iNGOs must be even more sophisticated in cultivating strategy and tracking the impact of their work — and their dollars spent.

With this in mind, Spencer Stuart’s Global Development & Social Enterprise team recently conducted a study in which we examined board effectiveness of a group of international NGOs. The purpose of this work was to elevate themes and best practices to alert the sector on how best to recognize inefficiencies and, in the long run, to make these crucial organizations more impactful. Through our decades of experience advising global boards of both private-sector and iNGOs, we have found common best practices that largely apply across the spectrum of these entities. We have put together a list of five board behaviors that can help iNGOs become more effective, efficient and, ultimately, successful in the New Year and beyond.

1. Plan early for succession

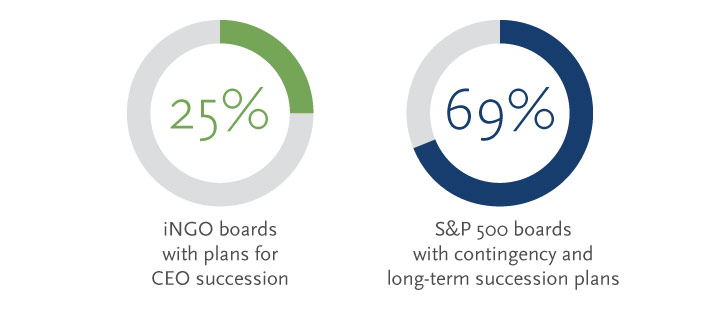

In our study of iNGO board effectiveness,1 we learned that only about 25 percent report having plans for CEO succession. Conversely, our research with S&P 500 boards found that 69 percent say they have contingency and long-term succession plans in place. The prevailing sentiment we heard from iNGO boards was typically along the lines of, “We just haven’t had the time to address it,” or from the CEO, a reticence to bring up CEO succession if it might suggest that the CEO is not committed to the post. However, we have consistently seen that proactive succession planning is one of the most important actions that a board can take to ensure a smooth leadership transition and to maintain a consistent long-term strategic vision. The CEO also demonstrates strong leadership instincts by helping to secure the future leadership in driving this discussion.

The importance of discussing and establishing a thoughtful plan for CEO succession cannot be overstated. An organization that is blindsided by a CEO’s departure, for example, can be left reeling if the board does not have a plan in place. An immediate, unplanned vacancy means the board will not have the luxury of time to conduct a thorough search, which could lead to a less-than-ideal replacement hire.

When boards do not have a good handle on the timing of the CEO’s retirement plan or a strong sense of the internal succession candidates, they can find themselves in a bind when the CEO’s departure is rapidly approaching. It is a difficult scenario for boards if, for instance, the CEO plans to retire in less than a year and assessments reveal significant gaps in the top contender’s capabilities or experience, or the board simply does not feel comfortable with the internal candidates. This can happen when the CEO gets ahead of the board and hones in on a particular succession candidate, and the board and CEO disagree about the strength of that internal candidate — or the process did not start soon enough to provide sufficient time to identify and address the development needs of internal candidates. It can also be the result of the unexpected emergence of an activist who forces an accelerated CEO transition. When internal candidates have “unfixable” weaknesses or lack the time to address developmental needs in time for the transition, it increases the likelihood that the board will have to look externally.

Once the idea is opened, CEO succession can be addressed by ensuring the organization has a pipeline of high-caliber executives rising through the ranks and a set of well-defined requirements for future leaders. No organization is too small to be thinking about this core best practice. It is also important that the board rigorously assesses internal and external candidates, conducts precise comparisons to external benchmarks and creates a meticulous transition plan. (We offer additional in-depth advice from corporate boards about this issue here.)

2. Set performance expectations with thorough self-assessment

In our work with boards, we have found that it is critical for boards to be held accountable for their performance. To ensure the group and individual directors are functioning effectively, boards should conduct annual self-assessments that take a clear-eyed look at their strengths and areas for development. For a fresh, unbiased review, a board should have external groups conduct assessments of individual members and the board as a whole every three years. (Learn more insight about board assessments

here.)

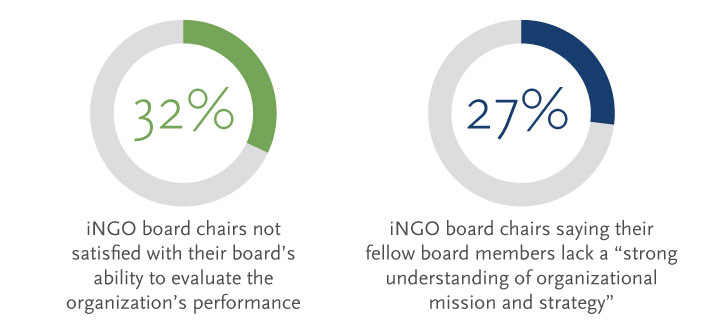

We have found that iNGOs benefit from these analyses, where one of the primary goals is to enhance the relationship between the board and management. This is clearly a pain point for iNGOs — our research found that 32 percent of board chairs surveyed are not satisfied with the board’s ability to evaluate the organization’s performance, and 27 percent say their fellow board members lack a “strong understanding of organizational mission and strategy.” This lack of alignment can have several repercussions, such as a diminished ability to engage in a well-informed exchange on operating priorities and the competitive landscape, as well as a weakened ability to prioritize key activities or issues of the organization. A board assessment, especially one that is conducted by an external evaluator, can identify opportunities for improving alignment between the board and management and ways they can work together more openly to set reasonable priorities.

In our conversations with the most aligned CEOs and board chairs, we witnessed dimensionally different thinking in regards to holding themselves accountable to the rigors of consistent assessment. Some shared that they keep a list of the 10 practices of a well-functioning board on each board agenda, so that the discussion topics relate back to these practices. Yet another pair shared that, given the pace of advancement in the fourth sector, “Our sector needs to wake up and realize that if we invite in performance standards, it means that garbage won’t get paid for — and it shouldn’t!”

3. Commit to using best practices — and the best people

There are myriad differences within iNGOs in size, operating breadth, funding, market/mission and history, so the composition of iNGO boards varies greatly. One constant, as with any governing group, is the need for boards to have a wide variety of experience, perspectives and skills to enhance the collective oversight of the organization. Therefore, a diverse group of directors is an essential part of a high-functioning board. Also, studies have found that organizations with diverse boards achieve better results than more homogenous groups. In addition to gender and racial diversity, there should also be a variety of styles — for every director who hews to the status quo, there should be a challenger; for every left-brain analytical, systems-thinker, a right-brain creative, free-thinker.

As we examined iNGO boards and compared them with corporate boards based in the United States with global businesses, we found the iNGO boards reflect greater and more consistent gender and racial diversity. As such, we underscore the importance of taking cultural variables into account: when speaking with some CEOs, they commented that directors from Africa and Asia often tend to be quieter around the board table amid the more demonstrative Westerner counterparts. Yet when these directors are drawn out by the board chair to speak, or when specifically asked to contribute expertise, those who come from these regions often provide invaluable insight into the ways in which the competitive universe operates and the politics of a group, state or nation that are materially relevant to the iNGO’s success and potential impact. It is essential that all perspectives not only be present, but heard.

The best iNGO boards will also consider their long-term strategy so they can ensure their directors have the vision to help them move forward. Boards, then, have several issues to consider when bringing on new members: first, the board must ensure directors can provide valuable insight in specific areas, such as regional expertise, domain knowledge from specific corporate or stakeholder experience, and specialized work in functions such as finance, technology, consumer channels and market access. Beyond that, all directors should contribute to the broader direction, including actively participating in discussions about the strategic direction of the organization.

In our research, we found that board engagement was enhanced when the group placed members into specific working groups with a delegate from the senior management team and tackled a strategic problem. The directors became involved and worked dynamically to problem-solve from their respective repository of experiences, while facilitating a knowledge-sharing experience with the executive leadership.

4. Create an open, collaborative board culture

Many factors go into a board’s culture, including the organization’s history, tone of leadership and size of the board. Culture is a key component in a board’s efficacy, as it can affect director behavior, risk appetite, decision-making processes and more. A transparent, well-managed culture can create an environment that encourages open discussion and supports dissenting views while keeping a collegial atmosphere, which can trickle down to the rest of the organization via “the tone at the top.” A dysfunctional culture, however, can give rise to negativity and disrupt harmonious dynamics throughout the organization.

A common issue facing boards is the tendency to fall into “group think,” in which most issues are met with unanimous agreement. To create a productive board culture, dissent must be encouraged and not seen as indicating a combative personality. Directors must be able to voice opinions and concerns without raising eyebrows around the table. A stifling feeling of uniformity can squelch crucial discussion — as Home Depot co-founder Ken Langone has noted, “no one wants to be the skunk at a lawn party.” (Read more about the importance of board culture here.)

5. Select strong leadership

Our research has reinforced that a strong leader, especially in the role of the board chair, is crucial to a board’s efficacy. While iNGOs may have been more homogenous as recently as five years ago, often elevating a board chair who was simply designated as the person with the most time to volunteer, the pace of change in the sector has introduced new leadership. Many of those at the helm of the organizations we surveyed were new to the role of chair, within a few years, and in those cases, fully acknowledged the age of disruption and the need for experienced leadership in this position. Interestingly, there was a strong correlation between those chairs who had some private sector experience and an increase in the board’s efficacy. These chairs can bring a broader range of perspectives and financial acumen that lift the board’s performance. The chair also has a significant effect on the board’s culture and tone, and by setting the agenda attuned to best practices, the chair ensures the board is addressing the right topics at the appropriate level.

Each of these leaders projected a collaborative style, and it was confirmed with their CEOs that they set a united tone that welcomes open disagreement while ensuring the discussion remains positive and constructive.

Conclusion

Boards clearly differ on many levels, but certain best practices apply across the spectrum and can help create productive boards that provide sound governance and forward-thinking strategic vision. Some of the steps may be difficult — encouraging dissent, for instance, can lead to uncomfortable conflicts, while creating an extensive CEO succession plan is an arduous — yet essential — process. In addition to these logistical best practices, though, the relational dynamic is crucial — a highly functioning board doesn’t just happen. It requires a diverse group that is willing to assess its own behavior as well as thoughtful oversight by a strong leader who encourages rigorous, open discussions. With these key roles considered, iNGO boards will head into the New Year effective, aligned and improved.

1 In 2017, we conducted a study of global iNGOs with the following four attributes: 10+ global offices, more than $50m in annual revenue, based in the U.S. and funded by diverse stakeholders including public and private sector organizations, bi-/multi-lateral and other NGO collaborators/funders.

Anne Simonds leads Spencer Stuart’s efforts at the intersection of global development and social enterprises, aligning the firm’s corporate, nonprofit and public sector networks. A member of the Education, Nonprofit & Government, Healthcare Services and Healthcare practices, she specializes in CEO and president searches and board and leadership advisory engagements for organizations worldwide. Reach her via email and follow her on LinkedIn.