A healthy board culture is increasingly recognized as an important element of board performance. But unlike other areas of board governance — composition, risk, succession and strategic planning or financial reporting, for example — board culture is less clearly defined and understood.

When asked about their culture, boards tend to speak in generalities, describing it in terms such as “collegial” and “engaged.” While true, those descriptions apply to many boards and don’t go deep enough in distinguishing one board from another — or provide the insight boards need to understand the role the culture is playing in overall board performance.

Two related forces have made the topic of board culture more urgent for many boards: growing stakeholder scrutiny on board performance and increasing board diversity.

In the past several years, shareholder activism has been gaining momentum. Investors around the world have become more active and vocal, seeking deeper engagement with the companies they invest in, using their influence to drive improvements in governance and holding boards to account on a wide range of issues, from strategy and performance to composition and CEO pay.

With less implicit understanding among directors about how the board should behave, it’s more important than ever to define and manage a board culture.

In some regions, the increase in board diversity is an outgrowth of investor pressure on performance. With research showing that companies with more diverse boards perform better, many investors are pushing boards to increase their diversity, especially gender diversity. Boards themselves recognize the value of injecting a broader set of perspectives into boardroom conversations, and are adding directors from other countries or different industries or increasing the gender, ethnic or age diversity of their composition.

Boards are adding new perspectives to enhance board deliberations and improve outcomes, but greater diversity also increases the opportunities for misunderstanding and conflict among directors with different points of view and backgrounds. In the past, boards tended to be more homogeneous and, as a result, there typically was more implicit agreement about how directors should interact and behave. Directors’ shared assumptions and similar experiences made decision making more efficient.

Today, with less implicit understanding among directors about how the board should behave, it’s more important than ever to define and manage a board culture to facilitate constructive interactions between board members. For boards striving to be more dynamic, performance-oriented and shareholder focused, getting culture right is key.

Board cultures tend to be more heavily weighted in one of four main culture styles: Inquisitive, Decisive, Collaborative or Disciplined.

What is board culture?

A board’s culture is defined by the unwritten rules that influence directors’ interactions and decisions. These include the mindsets, hidden assumptions, group norms, beliefs, values and artifacts (such as the board agenda) that influence the style of director discussions, the quality of engagement and trust among directors, and how the board makes decisions. Board culture also is influenced by the style of the board chair and/or the CEO. Boards can vary by region; in some national or regional cultures, for example, a more direct style is well-accepted, but in others, a more “diplomatic” approach is expected in the boardroom. Absent a dramatic change to composition — from a merger or addition of activist-backed directors, for example — board culture tends to evolve slowly because boards meet and interact intermittently.

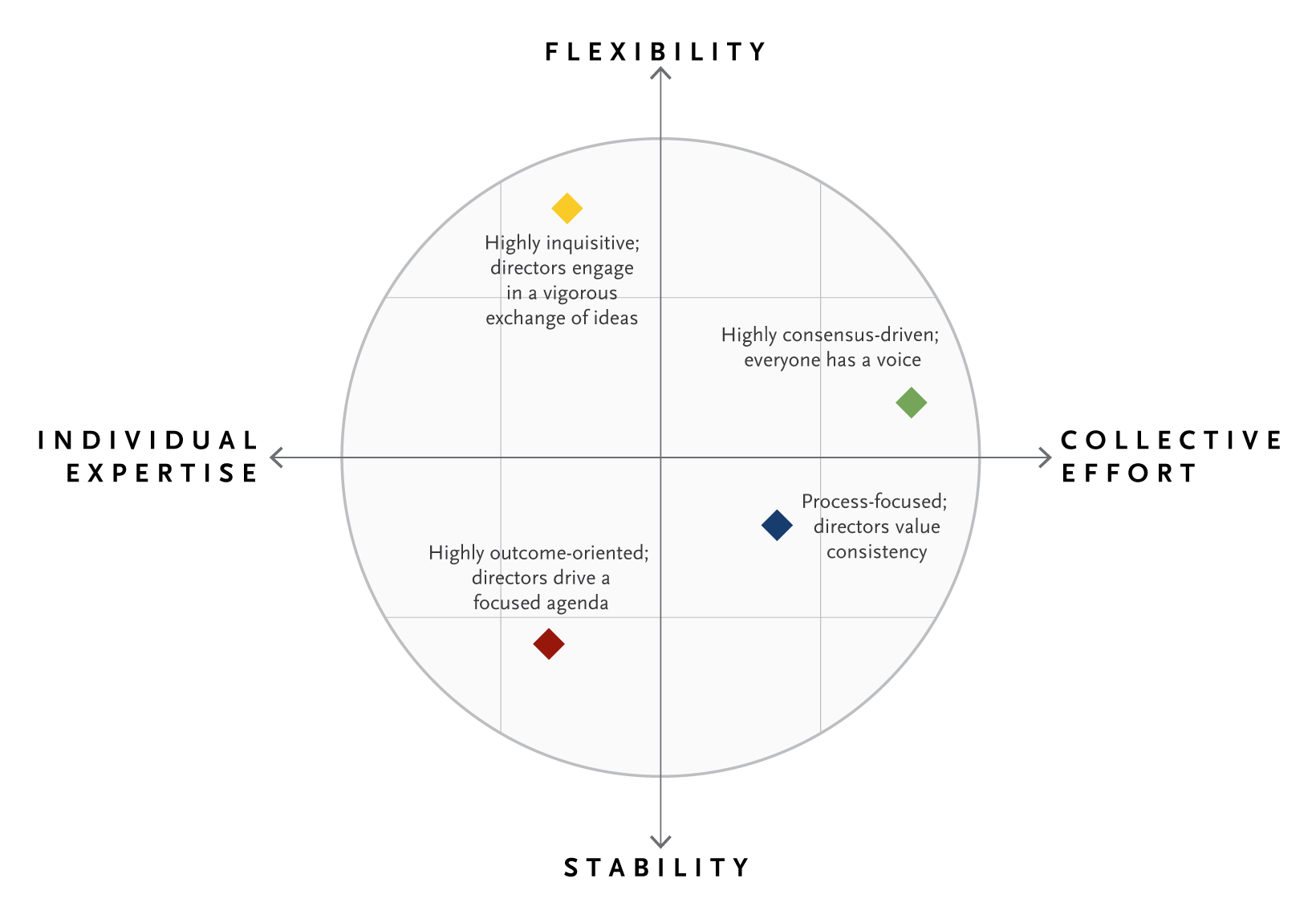

We have developed a model for diagnosing and understanding board culture, drawing on extensive research showing that there are two dimensions of culture: attitudes towards people (individual versus collective) and change (flexible versus stable). These same dimensions can be used to evaluate organizational and team cultures as well. In fact, a comprehensive study1 of organizational culture and outcomes found that companies can define and create an optimal culture that leads to better business outcomes when they have a framework for evaluating culture and the tools to manage it. We have found that many of the same principles apply equally well in the boardroom.

In practice, we observe a wide range of working styles and dynamics in the boardroom, yet in our experience, board cultures tend to be more heavily weighted in one of four main culture styles:

-

Inquisitive: These boards value the exchange of ideas and the exploration of alternatives.

-

Decisive: These boards are focused on measurable results, driving a focused agenda and outcome-oriented decisions.

-

Collaborative: These boards value consensus and having a greater purpose.

-

Disciplined: These boards emphasize consistency and managing risks and prioritize planning and adherence to protocols.

None of these styles is objectively better or worse than any other. The culture of a board should align with the business strategy and broader business environment and the requirements for working effectively with management. For example, companies in very dynamic industries, when strategy must be reviewed and reinvented frequently, may benefit from a board culture that is more inquisitive and flexible, where directors question assumptions and value the exchange of ideas. When managing risk is a top priority, boards may need to be more disciplined about monitoring results and performance, and following established protocols to ensure the accuracy of disclosures.

How to change board culture: four questions to consider

Because board culture is an important driver of board performance, a natural time to assess board culture and how it supports strategy is during the board’s annual self-assessment. Using an agreed-upon framework and vocabulary like the one Spencer Stuart has developed, boards can diagnose their current board culture and agree on a target culture. A board may want to evolve its culture if it is underperforming, when there is a new CEO or its own composition is changing, or when the business strategy is changing. For example, in a crisis or turnaround situation, a board may want to be more decisive and results-driven. At a strategic inflection point — when the organization needs to figure out new markets, new products, where to invest in acquisitions or innovation — a board may need to be more inquisitive and flexible.

Once the board has identified a target culture, directors can ask the following questions to help shift the board culture.

Do we have the right people in the boardroom?

Boards consider a variety of factors when recruiting a new director. When they want to evolve board culture, boards can consider an additional lens: how a director would help shift dynamics in the boardroom toward the desired culture. For example, a board that wants to become more decisive and results-driven may want the next director to have a no-nonsense, by-the-numbers style, perhaps a CFO profile. A board wanting to become more adaptive and inquisitive may look to add an entrepreneur or an innovator.

Are we structuring our discussions and assignments to focus on the right issues and activities?

Boards can reinforce their priorities by structuring committee and board assignments and meeting agendas in a way that supports the culture they want to create. A board seeking greater collaboration and openness to the ideas of all members may want to close discussions by “going around the table” and soliciting comments from each director.

Do board and committee leaders model the desired board culture?

The board chair has a profound role in shifting the board culture. The chair (or lead independent director) can move topics requiring the most board focus and energy earlier in the agenda, leaving the less strategic items to later in the meeting. If the board needs to become more inquisitive, the chair may decide to reduce the time devoted to operational reviews to leave time for the exploration of strategic alternatives. On a board that has decided to become more disciplined, the chair can direct a change in the board materials and build more structure around discussion topics.

The board chair or lead independent director and the committee chairs also can influence culture by how they model the desired culture. When a shift is needed, board leaders can guide discussions differently, encouraging or cutting off discussion as appropriate. They also may evolve pre-meeting activities, for example, creating a mechanism for directors to ask questions in advance of a board meeting.

A board may want to evolve its culture if it is underperforming, when there is a new CEO or its own composition is changing, or when the business strategy is changing.

Do we as individual directors consider how we are contributing to the culture?

As directors become more comfortable with the language of culture and more self-aware of how they are promoting or working against the target culture, they can provide feedback to one another on behaviors that may need to change. Just calling attention to directors’ habits and assumptions can help the board adapt its behaviors. Depending on what’s needed, the board also could provide a coach, group training or individual training on topics such as decision making, trust building or communication styles. Boards can use their annual self-assessment to evaluate their progress in moving toward the preferred culture.

On an individual basis, directors can reflect on their own behaviors and whether they are helping to shift the culture. On a board that’s overly collegial or collaborative, for example, directors can consider whether they need to weigh in on every topic. Or if the board wants to become more inquisitive, directors can decide to speak up more.

Starting to understand your board culture

When it’s able to diagnose culture, a board can evaluate the role culture plays in board performance and consider whether there are elements of the culture that need to change. Having a common language about the culture and identifying directors’ preferred styles helps board members understand and adjust to the preferences of one another and make better decisions about the potential culture fit of new director candidates. To provide a sense of various board cultures based on our model, we have plotted several examples of board culture below.

1 “The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture.” Groysberg, Lee, Price and Cheng. Harvard Business Review. January/February 2018.